Within this article, Ivan Moody states that 'the impact of minimalism in Portugal has barely been studied; the establishment and subsequent institutionalisation of post-serial and other avant-garde thinking meant that approaches to other kinds of modernism – and whether or not ostensibly postmodernist approaches could be included in such categories – only gradually came to be employed, during the course of the 1990s. This article discusses the work of four composers, Luís Tinoco, Nuno Côrte-Real, Eugénio Rodrigues and Tiago Cutileiro, as part of this context.'

Luís Tinoco featured in Ivan Moody’s ‘FOUR PORTUGUESE MINIMALISTS? IBERIAN REFLECTIONS’ (Tempo 71)

6 November 2017

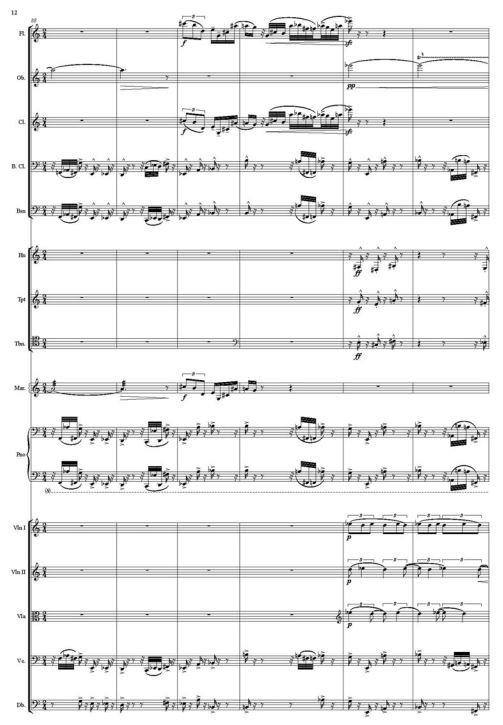

Within this journal, Ivan Moody accounts that “the work of Luís Tinoco, makes overt use of elements of the kind that Cutileiro considers ‘not truly minimalist’, within the context of a musical language that is both rich and diverse. The composer himself acknowledges, for example, the presence of certain gestures that come from minimalism, in such works as Short Cuts, Ends Meet, Invenção sobre Paisagem and Antipode, citing specifically Adams, Reich and Andriessen, but notes that he only began to examine minimalism as a phenomenon in depth when he began to teach at the Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa, some years after returning from London, where he had studied at the Royal Academy of Music with Paul Patterson. The composer whose work he points to as particularly influential before that time is Ligeti, as may be clearly heard in the early String Quartet (1995).

Nevertheless, Tinoco is anxious to point out that, ‘in spite of this connection which, I repeat, I consider more than legitimate, I think that it comes basically from my listening to Stravinsky and a great deal of jazz, in which there are obvious points of contact with the harmonic and rhythmic language of some minimal works’, noting that as a teenager he was an assiduous listener to the work of Pat Metheney and Lyle Mays, and that he maintains a very high opinion of Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock and Keith Jarrett. Certainly, jazz and Stravinsky may be heard as ancestors in some degree of a work such as Antipode (2000), but filtered in such a way as to suggest the music of Andriessen, particularly in terms of the repetition of motives that become ostinati, and the instrumentation, which favours saxophones and brass.

Tinoco says that he reclaimed the ‘gestures of repetition, ostinato and pulsation’ after discovering Ligeti’s Etudes, and points to his works Tríptico for violin and piano (1997), Verde Secreto (2007) for saxophone and piano, the wind quintet Autumn Wind (1998) and the quintet Light – Distance (2000) as proof of this. The fact that the dates of composition of these works covers an entire decade is proof of the enduring fascination of Ligeti’s work for Tinoco, but his music continues to be a highly eclectic mix, and in conversation he is as likely to locate his musical ancestry in Birtwistle as in Adams or Andriessen. When questioned about ideas of modernism and postmodernism, Tinoco says that his listening is broad in scope, as may be detected from the omnivorous nature of his musical references in the above, and that ‘official assumptions of position in art (and not only) are of little interest to me’.”

COPYRIGHT: © Cambridge University Press 2017

More news

17 December 2025

Three World Premiere Recordings of Works by Hilda Paredes

17 December 2025

Luís Tinoco’s Kokyuu Debuts to Critical Acclaim

11 December 2025

Hollywood Performance for David Lancaster's Canzone Sospesa

1 December 2025

Robert Saxton's ‘The Reckoning of Time’ premiers, released on Youtube.

26 November 2025

Belgian Premiere for David Lancaster's Jump Cut

26 November 2025

New CD for Luís Tinoco!

20 November 2025

A New Work by Sadie Harrison on Duo Tutti’s Forthcoming CD Release

14 November 2025

Danny Driver Performs Thomas Simaku’s Catena IV

27 October 2025

Two Australian Firsts for Sadie Harrison

22 October 2025

Outstanding reviews of Robert Saxton CD

18 September 2025

Welcome to UYMP's newest house composer!

26 August 2025

Creator Fund Award for Evis Sammoutis